A friend recently told me her yoga teacher ended class by saying, “Bhakti means self-love.” I winced. No, it doesn’t.

In an age when everything spiritual gets flattened into self-care, we’ve managed to turn one of India’s most radical, world-changing ideas into an Instagram caption. Bhakti—love offered to Krishna, the Supreme Person—has nothing to do with narcissism dressed up as healing. It’s about re-ordering the heart so that love stops orbiting the ego and starts revolving around something greater.

And yet, the confusion makes sense. Over the past century, Bhakti’s deep currents, its theology, poetry, and discipline, have been repackaged for modern consumption, much like Buddhist meditation before it was reduced to feeling good, managing stress, or “manifesting abundance.” Bhakti was never meant to be stress therapy, although that may be a secondary benefit. It was meant to be a revolution of consciousness.

So the teacher in me thought it might be time for a little required reading. The following are books for anyone who has ever wondered: What is Bhakti Yoga? How did an ecstatic spiritual movement that began in medieval India become a playlist on Spotify and a slogan on a T-shirt? How does Bhakti, devotion, interact with reason and social conscience?

Here’s a reading list that can help answer those questions. Some titles explore Bhakti’s historical roots. Others trace its evolution through colonial India into the modern West. A few offer contemporary reinterpretations that restore its philosophical depth.

You don’t need to read all of them. Start with the one that calls to you, whether you’re drawn to sacred poetry, historical context, or spiritual practice. I promise, after reading even one, you’ll never again mistake Bhakti for “just being nice.”

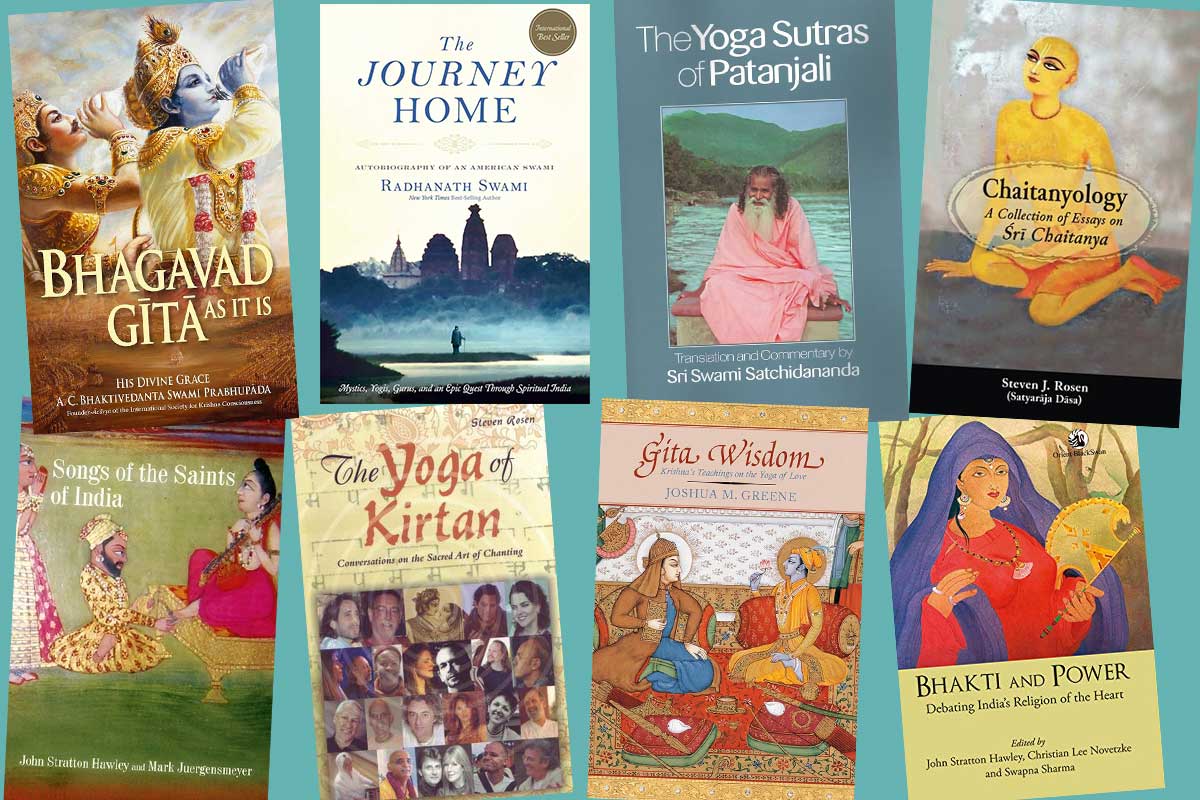

1. Bhagavad Gita As It Is

By A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada

What you will learn: The Gita is the philosophical root of Bhakti Yoga, a dialogue between Krishna and his warrior-disciple Arjuna that redefines action, duty, and love. Bhaktivedanta Swami’s translation and commentary restore the text’s devotional core, which many modern versions gloss over.

The payoff: You will discover how the Gita’s central teaching, selfless action in loving service, turns ordinary life into a sacred offering.

2. The Journey Home

By Radhanath Swami

What you will learn: A modern memoir tracing an American seeker’s path from the 1970s counterculture to deep immersion in Bhakti practice.

The payoff: Proof that Bhakti can thrive in the modern world—not as nostalgia for the East, but as a universal language of love and service.

3. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Translated and introduced by Edwin Bryant

What you will learn: In this edition of the classical text that shaped yogic philosophy long before the modern wellness era, Bryant’s translation highlights the devotional threads often neglected in secular readings of the text.

The payoff: Bhakti (devotion) and Jnana (study, knowledge) were never rivals. The sages saw love and clarity as twin paths toward the same realization.

4. Chaitanyology: Writings on the Transformative Teachings of Sri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu

By Steven J. Rosen

What you will learn: A lucid, contemporary exploration of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu’s philosophy of bhakti, divine love, drawing from scripture, music, and modern scholarship. Rosen unpacks how Chaitanya’s vision of ecstatic devotion shaped Vaishnava theology and still informs global Bhakti culture today.

The payoff: A bridge between past and present—showing how a 16th-century saint’s message of humility and joy continues to speak to seekers living in a fractured world.

5. Songs of the Saints of India

Translated by John Stratton Hawley and Mark Juergensmeyer

What you will learn: Selections from the great medieval poet-saints, including Mirabai, Tukaram, Surdas, and Kabir, who sang of divine love in vernacular tongues, defying caste and convention.

The payoff: Their verses are as raw and urgent as the blues. You will feel Bhakti as both social protest and mystical awakening.

6. The Yoga of Kirtan

By Steven J. Rosen

What you will learn: A collection of in-depth interviews with leading kirtan artists such as Krishna Das and Jai Uttal, revealing the personal histories, philosophies, and experiences behind Bhakti chants.

The payoff: This book restores the soul to what has too often become performance. It’s a living portrait of Bhakti practice as sound, surrender, and shared joy.

7. Gita Wisdom: An Introduction to India’s Essential Yoga Text

By Joshua M. Greene

What you will learn: A brief modern retelling of the Bhagavad Gita in contemporary language, exploring how its ancient message of selfless love can guide modern life.

The payoff: The Gita’s teachings on Bhakti aren’t about escaping the world; they are about elevating it and turning daily duty into sacred offering, and love into a practical philosophy.

8. Bhakti and Power: Debating India’s Religion of the Heart

Edited by John Stratton Hawley

What you will learn: Scholars debate whether Bhakti was a challenge to power or a tool of it—an uncomfortable but essential conversation.

The payoff: This collection reminds us that love, when authentic, is never sentimental. It is disruptive, demanding, and socially transformative.

Your assignment

Pick one book that speaks to you. Read it not as a spectator but as a participant. For extra credit, read two, and you may find yourself doing something quietly radical in the year to come: loving the world not for what it gives you, but for what you can give back.