I have a confession to make. After teaching the Bhagavad Gita for nearly a half-century, I rarely know if my classes make any practical difference to anyone. Then this happened.

A recent Zoom session drew about twenty participants from different parts of the world. The theme was “perfection”—in Sanskrit purna or “complete” and “without defect”—and right from the start, there was broad agreement that perfection was not a very appealing concept. It felt oppressive. The notion of somehow rising above all mistakes and failures was a fantasy, more discouraging than inspiring.

The Gita does point toward something beyond imperfection. The atma, or eternal self, is perfect in the sense that it is not made of matter, not subject to decay or death. Still, the imperfect material world is the only reality most of us know. And in this world, striving for perfection—or even for just becoming better—can feel like chasing an ever-receding horizon.

It was in this context that one participant, a counselor from Lebanon, spoke up. She works with refugee families, many of whom come from cultures where violence is so pervasive, abuse of children is considered normal and routine. She described how one family punished their child for a small infraction by locking her in an attic for days. Another family punished their son for minor misbehavior by burning him with coals. The counselor’s voice cracked as she described what she had witnessed.

In a voice barely audible, she said, “I find myself having to advise the parents that instead of locking their daughter away, ‘why don’t you just hit her with a soft slipper?’ Or to the other family, ‘Try slapping your child instead of burning him.’ It’s horrible, the things I have to tell them, but these are the only alternatives they might consider. Sometimes, doing less harm is the only way to make any progress—and that’s why these Gita discussions help me so much. Arjuna did not want to fight, but he was forced to compromise, so he fought but as humanely as possible, without any intention of prolonging pain or suffering. The world we live in forces us into such situations. Sometimes all we can do is choose to do less harm. Studying the Gita has helped me live with what I have to do. So, I thank you.”

Her confession made dramatically clear that values and vocabulary in the Gita—terms such as karma, dharma, gunas, kleshas—are not idealized abstractions but the real grit of human life, where moral clarity is not always obvious, and perfection is an impossible dream.

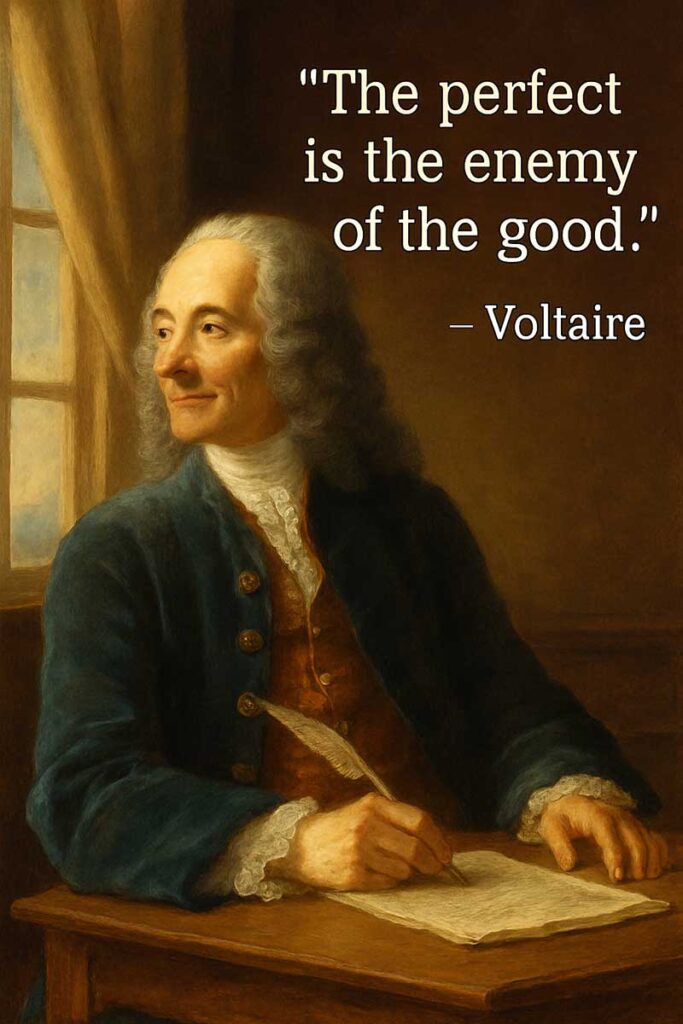

As the session drew to a close, we all agreed: the Gita does not insist that we become flawless, only that we strive for progress and that we act with realistic expectations. As the French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) put it, “Do not allow the perfect to become the enemy of the good.” Perfect, purna as defined in the Gita, means making a perfectly heartfelt effort—however imperfect it may be.

The counselor’s stories reminded us that incremental progress is the only kind, and that doing good, even a little good, is the perfect way to keep a light burning in an often very dark world.

____

Joshua M. Greene (Yogesvara dasa) is author of Gita Wisdom: An Introduction to India’s Essential Yoga Text. His next book is Golden Avatar (Mandala 2027) about the life and teachings of Sri Chaitanya (1486-1533).