Share this page

Swami in a Strange Land

How Krishna Came to the West

Into the turbulent 1960s with its civil rights marches, anti-war demonstrations, and challenges to traditional American life stepped 70-year-old Bhaktivedanta Swami, on a mission to save the world. He arrived by cargo ship, having suffered two heart attacks on the storm-tossed ocean journey from India. He had seven dollars to his name, knew no one, and had never been outside his homeland. But he was determined to spread the teachings of Krishna, the Supreme Being of the ancient Vedic scriptures.

He passed away twelve years later. By then, “Prabhupada” (as he was called by admirers) had built an international movement with millions of followers, translated dozens of Sanskrit sacred texts, established hundreds of centers to Bhakti (devotional) yoga, and made Krishna a household name through popular recordings and street chanting parties. The path to self-realization has never been the same.

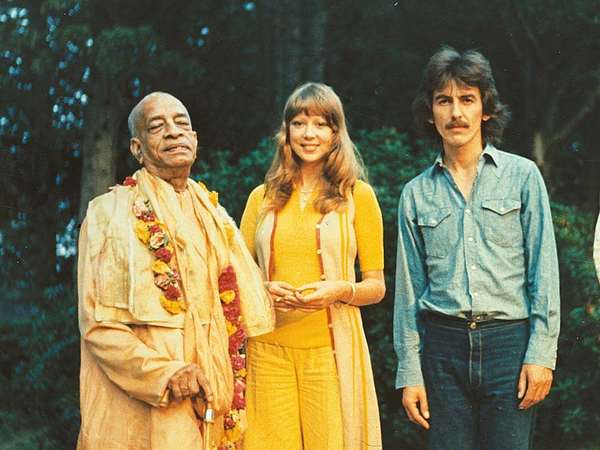

Swami in a Strange Land shows why cultural icons such as Beatle George Harrison and poet Allen Ginsberg embraced Prabhupada’s teachings, and why millions more have embarked upon the path of bhakti yoga in his footsteps.

Watch

the book trailer

Praise for swami in a strange land

Alfred B. Ford

Board Member, Ford Motor Company

"Joshua Greene wonderfully tells this story of timeless love."

Radhanath Swami

"The true, thrilling adventure of a modern-day spiritual giant."

Sharon Gannon

"A story one would not believe if it were not a fact."

Klaus K. Klostermaier

Appreciations for Bhaktivedanta Swami

"One day I just realized, God, this man is amazing!"

George Harrison

"Swami Bhaktivedanta brings to the West an authentic metaphysical consciousness."

Thomas Merton

"Swami Bhaktivedanta -- what kindness, humility and intelligence!"

Allen Ginsberg

Chapter Excerpts

The Reckoning

Thirty-six days later, after traveling 12,000 miles, the Jaladuta arrived in Boston harbor. The Coast Guard saluted the crew as they disembarked. Sailors unloaded cargo, and the following day the ship departed for New York. At noon on Sunday, September 19, 1965, Swamiji stared out at skyscrapers lining the New York horizon like giant concrete teeth. He took out his pen and composed a poem in his native Bengali. “My dear Lord Krishna,” he wrote, “I guess you have some business here, otherwise why would you bring me to this terrible place? Now it is up to you to make me a success or failure, as you like. I am just like a puppet in your hands. So if you have brought me here to dance, then make me dance — make me dance, O Lord. Make me dance as you like.”

Read more

From his bag he chose a dhoti — a three-yard length of cotton cloth dyed saffron, the color of a Vaishnava monk — and put on white rubber shoes and dressed with care. He said goodbye to the captain and crew and thanked them for their hospitality. Then he arranged for the two hundred sets of his books to be stored in the Scindia warehouse. If somehow he were able to sell a few copies, he would use the money to cover expenses for however long he stayed in America. Then, with nothing but his tiny suitcase, bag of cereal and an umbrella tucked under his arm, and holding the railing as firmly as his recovering muscles would allow, he stepped off the Jaladuta and into the future.

THE AGARWALS HAD ARRANGED for a representative from Traveler’s Aid to meet the Swami on his arrival, and together with the agent he set out together for Port Authority Bus Terminal. The Swami had sold a set of his books for twenty dollars to the Jaladuta’s captain, enough to purchase a ticket for Butler, Pennsylvania, where the Agarwals lived with their infant son. Along with a letter of sponsorship, the Agarwals had extended an invitation to stay for a few weeks in their Pennsylvania home as a way of adjusting to life in America. On the bus, the Swami watched an endless stream of cars fill the highways exiting New York City. He traveled past skyscrapers and slums, past billboards and blackened industrial zones and miles of factories that lay between New York and Pennsylvania.

America’s four-hundred-year history revealed itself to him with every passing mile. Pioneers had made their way across the Atlantic seeking religious freedom in a land of their own. They crafted homes of wood cut and carved with their own hands, plowed the earth, offered prayers of thanks and built a nation like none other in human history. Generations came and went, and their descendents swapped their ancestors’ noble purpose for the chance to bore through mountains and urbanize vast tracts of land. They spent fabulous sums constructing coast-to-coast highways, soaring skyscrapers and dense cities that concentrated millions of people into vertical mazes of concrete and glass. Inspired by advances in technology, they evolved a new ethos. Americans were no longer caretakers of the earth but its masters, competing with one another for profits and goods. They turned their backs on covenants with the natural world, gouged the ground for oil, pillaged forests, built slaughterhouses, churned out weapons, conquered foreign lands and made of the world one huge market. Money was their God — the same one India now worshiped.

The Swami looked at the vista of this strange land whizzing past his window and knew there would be a reckoning. Once the Americans exhausted their fantasies about finding contentment in material things, they would emerge from their offices, clubs, shopping malls and restaurants and wonder what went wrong. When the veil of illusion fell away, when the reality of old age and disease and the sad brevity of a lifetime at last penetrated, the meagerness of their lives would become clear — and that would be the moment for Krishna consciousness, the lifeline that could save them from drowning in an ocean of repeated births and deaths. He had come for this purpose, to make the message available. Wake up, the Vedas declared. Don’t remain in darkness. Come up to the light!

The Physics of Consciousness

DR. RICHARD L. THOMPSON, PhD, grew up among people who had eliminated God from their lives: his parents went to church but didn’t believe what they heard there and their indifference to religion rubbed off on him. By the time he was in high school, Thompson was drawn to science. The more he heard science’s explanation of life, the more science, too, lost its allure. The notion that consciousness could be explained by patterns of oscillating molecular balls and springs made no sense to him. He looked forward to college. “That’s where I’ll find satisfying knowledge,” he thought.

Read more

In college, things got worse. The professors seemed even more convinced that all natural phenomena could be described by mathematical laws. The universe and life itself, according to them, were products of a cold, impersonal natural order. Tall, studious and gifted with a keen intellect, Thompson looked at problems from unusual angles. He was convinced modern science was wrong to define life in purely mechanistic terms and set out to find a better explanation of how reality operated. If traditional institutions of higher learning had no satisfying answers for life’s Grand Questions, there had to be other places he could turn.

In college, things got worse. The professors seemed even more convinced that all natural phenomena could be described by mathematical laws. The universe and life itself, according to them, were products of a cold, impersonal natural order. Tall, studious and gifted with a keen intellect, Thompson looked at problems from unusual angles. He was convinced modern science was wrong to define life in purely mechanistic terms and set out to find a better explanation of how reality operated. If traditional institutions of higher learning had no satisfying answers for life’s Grand Questions, there had to be other places he could turn.

In 1969, while earning his Master degree in mathematics at Cornell University, Thompson read books on Indian philosophy, including a copy of Bhaktivinode Thakur’s biography of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. Each individual soul, the book described, was a spark of non-material energy, simultaneously one with and also different from Krishna, the Supreme Person. That struck a chord with Thompson. The idea that consciousness originated not from matter but from a higher order of energy appealed to him.

He next came upon a book with the intriguing title Easy Journey to Other Planets, first published in India in 1960, and was fascinated by its origins. The author, A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami, had read in an October, 1959, issue of the Times of India that two physicists from the University of California had received the Nobel Prize for a startling discovery. Some particles, the physicists announced, were coupled with other particles spinning in reverse orbit. The physicists concluded there must exist an anti-material world parallel to our own world. They further theorized that, as pure energy, anti-material particles might prove to be an ideal fuel for interplanetary travel.

As a former pharmacist, Bhaktivedanta Swami understood the value of science on its own terms. After all, doctors did good work without having to invoke supernatural forces. Still, the Times of India article prompted the thought that contemporary scientific language might serve to convey to Western audiences the Vaishnava perspective on consciousness. Terms in the Times of India article suggested poetic equivalents: souls as “anti-material” particles, the spiritual universe as an eternal realm “spinning” opposite to the world around us, mystic yoga as a path to “interplanetary travel.” The Swami wrote a thirty-eight-page essay called “Easy Journey to Other Planets,” later published as the book Thompson had found.

“The latest desire man has developed,” Thompson read in Easy Journey, “is the desire to travel to other planets.” Such a desire was natural, since the soul originally belonged to an “anti-material world” where life is eternal, blissful and fully self-aware. The desire for interplanetary travel could be fulfilled by the process of Bhakti Yoga — the highest of all yogic processes.

The book went on to explain that, like antimatter, the “anti-material world” of the soul could only be understood by moving past realities felt and seen, to realities intuited. The secrets of creation would not be found with electron microscopes and orbiting optical telescopes, which were hampered by the limitations of human perceptions and thought, but by inner experiment.

Farther down, below the realm of short-lived subatomic particles, Easy Journey explained, on the most fundamental levels of creation lay an indestructible reality. This was the realm of consciousness, that part of life which was never annihilated. The Svetasvatara Upanisad gave an exact measurement: the dimension of the soul was “one ten-thousandth of the tip of a hair”. Too small to be perceived by material tools, this indestructible particle of non-material energy was so powerful that it illumined the entire body with consciousness. “The scientists’ conception of antimatter,” Easy Journey continued, “extends only to another variety of material energy, whereas the real antimatter must be entirely anti-material and free from annihilation by its very nature.”

Easy Journey quoted the Bhagavad Gita’s description of two forms of energy: one inferior (apara-prakriti) and the other superior (para-prakriti). The soul is formed of superior or anti-material energy and can never be destroyed. “Because of the presence of this anti-material particle, the material body is progressively changing from childhood to boyhood, from boyhood to youth to old age, after which the anti-material particle leaves the old, unworkable body and takes up another material body.”

Easy Journey then described that “as material atoms create the material world, so the anti-material atoms create the anti-material world with all its paraphernalia.” By using what astrophysics might later describe as black holes, master yogis “give up their material bodies at will at a certain opportune moment and can thus enter the anti-material worlds through a specific thoroughfare which connects the material and anti-material worlds.”

From the Vedic perspective, the book concluded, interplanetary travel depended not on technology but on mental preparation. “Scientists who explore outer space in an attempt to reach other planets by mechanical means must realize that organisms adapted to the atmosphere of the earth cannot exist in the atmospheres of other planets. One can attempt to [inhabit] any planet he desires, but this is only possible by psychological changes.”

Easy Journey cited the Bhagavad Gita’s prescription for travel between worlds: “That upon which a person meditates at the time of death, quitting his body absorbed in the thought thereof, that particular thing he attains after death.” Such transfer to other worlds takes place instantly, at the speed of mind, and for a master yogi it is “as easy as an ordinary man’s walking to the grocery store. By the grace of God, we have complete freedom. Because the Lord is kind to us, we can live anywhere — either in the spiritual sky or in the material sky, upon whichever planet we desire. However, misuse of this freedom causes one to fall down into the material world and suffer the threefold miseries of conditioned life. Easy Journey concluded that “Bhakti Yoga is the eternal religion of man. At a time when material science predominates all subjects — including the tenets of religion — it would be enlivening to see the principles of the eternal religion of man from the viewpoint of the modern scientist.”

IT WAS CLEAR TO PROFESSOR THOMPSON that the book was a semantic exercise but it was one that had required a bold, intuitive leap on the author’s part. Bhaktivedanta Swami, it seemed to him, had discovered a way to make use of scientific terminology to show the relevance of Vedic teachings. The book even alluded to the multiverse, a theory of infinite universes which had only recently made its appearance in scientific circles in 1960 when Easy Journey was first published.

On an emotional level, Thompson found Easy Journey exciting. Intellectually, however, he was torn. Was the Swami just trying to validate religious myths with science? “How could this stuff possibly be true?” Thompson wondered. “Life on other planets? Mystic space travel? This is so different from what I’ve been trained to believe all my life.”

Thompson was of that generation of twentieth-century scientists who had begun asking new questions since, for all practical purposes, science had reached the limits of its ability to see past the very small or penetrate beyond the very distant. What lay on the other side of those limits? Something more than the reductionist picture of the universe was going on; but for fear of being marginalized or losing their jobs, at that time none dared call it divinity. Twenty-two-year-old Richard Thompson walked the streets of Ithaca, New York, displaced from the world he knew yet uncertain about the world he had discovered.

“Just thinking science wrong and the Vedic view right — that’s not sufficient,” he concluded. “There has to be a way to reconcile the two. That would be important. If I’m feeling this way, there must be others who are torn by the contradiction between modern science and Vedic knowledge. If I can put those two things together, maybe I can help them, as well as myself.” Eventually, he approached the book’s author, A.C. Bhaktivedata Swami Prabhupada, for initiation and received the name Sadaputa Das. Over the next thirty years, Sadaputa dedicated himself to defining the relationship between science and religion.

“Some see it as one of inevitable conflict,” he wrote in the introduction to a collection of his essays, “others see it as harmonious, and still others see differences that they hope to reconcile. For many years, I was one of the latter. However, I have come to realize another potential relationship between religion and science. Both can cross-fertilize one another with inspiring new ideas that may ultimately culminate in a synthesis that goes beyond our understanding of either.”

In his career as a devotee scientist, Sadaputa emulated his teacher, Prabhupada, in pointing out the shortcomings of attempting to explain consciousness and complex biological forms in purely mechanistic terms. He would go on to write several acclaimed books that reconciled prevailing scientific perspectives with the Vaishnava viewpoint.

“I liked the third chapter of Mechanistic and Nonmechanistic Science very much,” wrote Eugene Wigner, a theoretical physicist who had won the Nobel Prize in 1963 for his contributions to the study of elementary particles. “In particular, it acquainted me with the Bhagavad Gita. I learned that the basic philosophical ideas on existence are virtually identical with those which quantum mechanics led me to.” Another Nobel laureate, Brian Josephson, best known for his pioneering work on superconductivity and quantum tunneling, admired Thompson’s “cogent arguments against the usual scientific picture of life and evolution.” Like his guru, Prabhupada, Sadaputa managed to shine a light on scientific anomalies while maintaining utmost respect for good science. “Because he loves science,” wrote a reviewer, “he is pained by its contradictions and seeks its intelligibility in a larger context.”

BY 1973, Prabhupada had initiated several scientist disciples and founded the Bhaktivedanta Institute, whose mission was to establish the Vedic viewpoint as scientifically defensible. “Our worship of Krishna,” he told them during a morning walk in Los Angeles, “is our internal affair. The external affair is to establish that life comes from life. Otherwise, atheistic scientists will misguide society. Because it is truth, you will come out triumphant, no doubt, but your work is to determine how to present it in a modern way.” Encouraging — and initiating — scientists became a seminal component of Prabhupada’s campaign to establish the Vedic viewpoint in the West.

In the Media

Articles & Interviews

Patheos - Spirituality Itself Series

SWAMI IN A STRANGE LAND: HOW KRISHNA CONSCIOUSNESS CAME TO THE WEST By Bridgitte Jackson-Buckley

Questions & Answers

with the author

All wisdom traditions teach one basic idea: reality is deeper than what we perceive. The unique contribution of Bhakti or devotional yoga is a tried-and-true, practical method for seeing that deeper reality, through chanting of sacred mantras, a healthy lifestyle, and the cultivating of a yogic way of life. What is the relevance of that message? Imagine living in full awareness of yourself as an immortal, invincible being. You are no longer the sum-total of your life’s traumas. They no longer define you. That awareness of ourselves as spirit-souls is energizing, exciting, liberating. It means going from doubts and uncertainty to self-confidence and action.

Prabhupada started chanting Hare Krishna in public in 1965 when he arrived from India at age 70. The consciousness-expanding influence of that chanting inspired many renowned artists to include it in their compositions. John Coltrane dedicated his final three albums to chanting and yoga. John Lennon included the mantra in “Give Peace a Chance.” Stevie Wonder has the chant on his album “Songs in the Key of Life.” The list is quite long. George Harrison popularized the Hare Krishna mantra around the world in his post-Beatles music. Most recently, an entire category of music—“Kirtan”—has emerged, and the more informed chanters acknowledge their debt to Prabhupada for having set the stage a half-century ago with the Krishna chanting.

Science and spirituality share a common goal: to reveal the mysteries of creation. Most sciences qualify their research by eliminating transcendent causes—in other words, no reference to souls or gods or anything that cannot be proven through research and experiment. Prabhupada saw that as a mistake. Sometimes he even called it dishonest and dangerous. He also understood why science is so intolerant of spirituality: it triggers emotional antipathy toward exploitative religion and blind faith. Real spiritual inquiry is not religion. That was his point. Real spiritual inquiry is science with the limitations removed.

In the mid-1960s, when Prabhupada first arrived in New York, there were very few yoga studios, vegetarianism was considered weird, and mantra chanting and meditation were viewed as practices for people on the margins of society. Now, these things are standard in progressive health and wellness regimens. Back then, Krishna devotees were viewed as lost souls. Today, they are professors teaching Hinduism in universities, credentialed representatives in areas of conflict resolution, environmental reform, and spokespeople for enlightened business. The influence of Krishna consciousness on American life is quite profound. From a single storefront in New York’s Lower East Side, the movement has expanded to more than 100 temples, a dozen farm communities, vegetarian restaurants, and community service organizations nationwide

People always ask me how I can reconcile my spiritual beliefs with what happened in Europe less than 80 years ago, I didn’t have a very good answer. It’s a real challenge justifying the purposeful vision of creation outlined in the Sanskrit texts with the reality of how people treat one another. Prabhupada was born in 1896. He lived through two world wars. I wanted to write a book that would convey how he was able to resolve that contradiction—so not just a book about the chronology of his life but about his teachings. It is, I believe, the same compulsion we feel to reconciling the smooth, predictable universe of Einstein with the chaotic, unpredictable world of quantum physics. There is a strong correlation between those two quests.

Books alone cannot change people. Black ink on a page is just that. But ideas, captured in a book and then explored in good company—what the Bhakti tradition calls sangha—that’s a powerful combination. From the outset, I had four goals for Swami in a Strange Land. I wanted readers to understand that

1) We are not our body but the consciousness that animates the body

2) The source of creation is also conscious

3) Prabhupada demonstrated what a real guru or teacher is

4) I’d like to find a sangha group to explore these ideas further.

I hope not. The sacrifices Prabhupada went through to do what he did—the years of struggle, of derision, of rejection by family and acquaintances, the dire conditions he endured, basically every reason to give up his journey—I wouldn’t want anyone to think they have to go through that to achieve enlightenment. But clearly sacrifice is needed. You can’t go to yoga class, then go out smoking and drinking, and think you’re going to get anywhere. In the words of Joe Campbell, we have to give up the life we want so as to embrace the one we are meant to lead. It starts with daily chanting of Hare Krishna, a simple prayer. Everything flows from that.

Very important. There is no question, for example, that George Harrison’s allegiance to Prabhupada as a teacher and George’s recordings of the Krishna mantra popularized mantra chanting in a powerful way. But was Prabhupada’s mission dependent on that kind of celebrity affiliation? Not at all. How many celebrities have come and gone over time? Yet the chanting is still there—not still there, growing constantly! We can say that thoughtful people—famous or not—see the power of Prabhupada’s teachings. He always said he had not invented anything. He was passing along wisdom that has been embedded in ancient texts from before recorded history. That humility was a big part of his appeal.

Social

Instagram & Facebook Images

Link information: Instagram: gitawisdom, Facebook: joshuayogesvara, Web: swamibio.com

Learn more

Hare Krishna The Film

Hare Krishna! is the true story of an unexpected, prolific, and controversial revolutionary. Using never-before-seen archival verite, Prabhupada’s own recorded words, and interviews with his early followers, the film takes the audience behind-the-scenes of a cultural movement born in the artistic and intellectual scene of New York’s Bowery, the hippie mecca of Haight Ashbury, and the Beatle mania of London, to meet the Swami who started it all.

BHAGAVAD GITA AS IT IS book

The Bhagavad Gita is the main source-book on yoga and a concise summary of India’s Vedic wisdom. Yet remarkably, the setting for this best-known classic of spiritual literature is an ancient Indian battlefield.

At the last moment before entering battle, the great warrior Arjuna begins to wonder about the real meaning of his life. Why should he fight against his friends and relatives? Why does he exist? Where is he going after death? In the Bhagavad-gita, Lord Krsna, Arjuna’s friend and spiritual master, brings His disciple from perplexity to spiritual enlightenment. In the course of doing so, Krsna concisely but definitively explains transcendental knowledge; karma-yoga, jnana-yoga, dhyana-yoga, and bhakti-yoga; knowledge of the Absolute; devotional service; the three modes of material nature; the divine and demoniac natures; and much more.