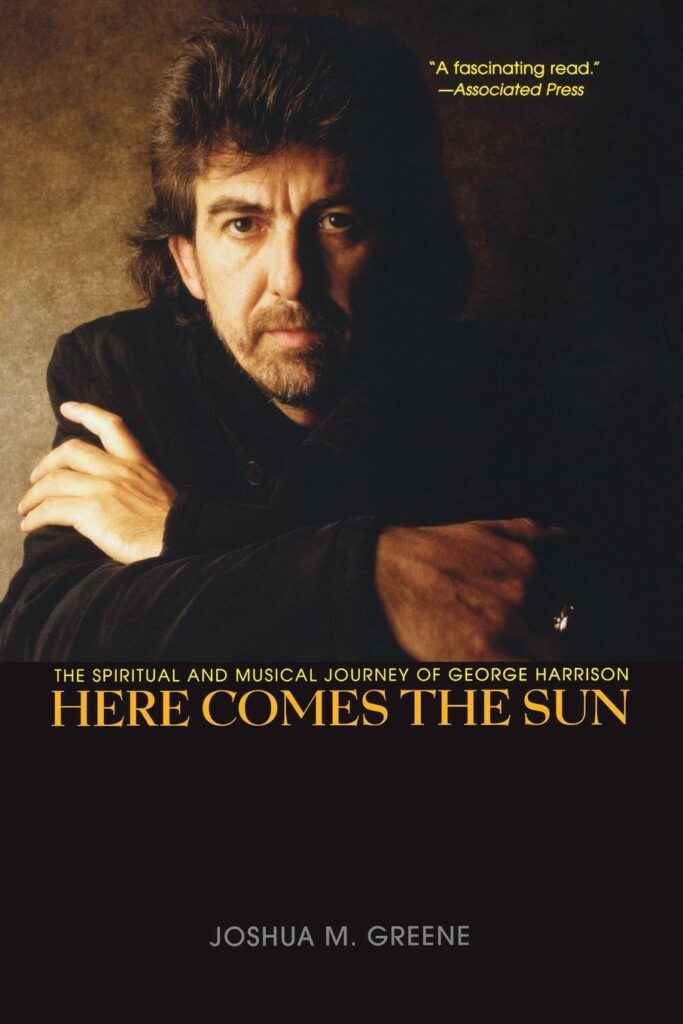

It is the fall of 1966. The Beatles have just held their last live concert, in San Francisco, and George Harrison has declared, “That’s it. I’m no longer a Beatle.” For the past several months, his discovery of yoga, meditation, and the sitar have pushed him in a new direction—away from the external world of pop stardom toward the internal world of self-realization.

From the window of their suite in Bombay’s Taj Hotel, George and his wife Pattie Boyd looked out onto a traffic jam of beeping cars, rumbling bullock carts, trumpeting elephants and ringing bicycles. Ravi Shankar arrived at the hotel, and George’s sitar lessons picked up where they had left off in England.

At first, no one in the hotel recognized him. But after a few days, overconfident of his anonymity, George took an elevator down to the lobby intending to do some shopping and drew the attention of a teenage elevator operator. Could it be? The next morning, George and Pattie awoke to crowds of Indian Beatlemaniacs outside their window shouting, “We want George!”

To find some privacy, George and company took a train north to the province of Kashmir, a lake-filled state bordered by Pakistan to the west and China to the north. Kashmir was the retreat of royalty, an idyllic land of fruit orchards and flowering gardens. The group took up residence in a large wooden houseboat on the largest of the city’s many lakes. Through carved wood windows, George looked out on the Himalayas rising in the distance and savored freedom from life as a Beatle.

Among the books that Ravi had brought was Raja-Yoga by Swami Vivekananda. In Raja-Yoga, George learned Vivekananda’s central message: all people possess innate and eternal perfection. “Tat tvam asi—That thou art,” Vivekananda declared. “You are that which you seek. There is nothing to do but realize it.”

One passage in particular held George’s attention. “What right has a man to say that he has a soul if he does not feel it, or that there is a God if he does not see Him? If there is a God we must see Him…otherwise it is better not to believe.” Better to be an outspoken atheist, Vivekananda advised, than a hypocrite.

George discovered that the word yoga meant “to link,” as in the English words yoke or union. In its early stages, he read, yoga involved physical exercises, but its goal was to link the soul with the Supreme Soul or God. To reach that goal a yogi must also practice yama or self-restraint, which included no killing and, by inference, a vegetarian diet; no lying; he must refrain from “stealing,” which by extension meant not taking more than needed. Along with qualities such as cleanliness, austerity and dependence on God, these formed the basics “without which no practice of yoga will succeed.”

True yoga, Vivekananda wrote, did not depend on being Christian, Jew, Buddhist, atheist or theist. The benefits of yoga were available to every human being through daily practice. Try to practice mornings and evenings, the revered teacher advised. Try not to eat before morning yoga is done. And try to control sex drive. When contained, sexual energy transforms into nourishment for the brain. Without chastity, one loses stamina and mental strength. Above all, never produce pain in any living being by thought, word or deed. “There is no virtue,” Vivekananda wrote, “higher than this.”

Where was George’s childhood now, or his career? What sense did the history of this one short life make compared to the eternity opening up before him? However exciting his achievements looked from the outside, something grand and majestic was transporting him beyond the minutiae of that world. What other people perceived of him—a working-class Liverpool boy who became part of history’s most successful rock group, who then married a top model and had more fans than Elvis—dwindled to mere facts. What he was finding in India spoke to the quintessence of experience, to the meaning and significance of his life.

The books George read in Kashmir kept him enthralled with their descriptions of powers lying dormant within the soul. He read essays on how meditation could lower metabolic levels, increase spiritual awareness, and eventually help the soul escape further reincarnations. As a child, George had little taste for reading. In Kashmir, he was rarely without a book in his hands.

He was twenty-three years old and as far back as memory allowed his sense of himself had been guided by what others told him, by childhood and family, by fame and by caricatures in the press. If, as he now read, he had nothing to do with any of those Georges, then who was he? If after this life ended, he did not end but moved on, precisely who moved on? His body would fall away and with it the accumulations of a lifetime, but he, the soul within, would remain. The books explained that the person he thought himself to be, the George whom others saw and judged, was real but temporary, a gross body built from five elements—earth, air, water, fire, and space—and a subtle body consisting of mind, intelligence and ego. It was his true self, the soul inside those coverings that provided the energy to make them work. At death, when the temporal coverings fell away, earth again merging with earth, water with water, air with air, that true self would move on to some other destination.

He had to share this knowledge with his mates. Pattie seemed happy to be there with him, but what about John or Paul or Ringo? Would they agree to spend time in India? And if they did, would they catch spiritual fire the way he had? There was no guarantee they would find those discoveries as meaningful as he did, and soon George Harrison would see that answering a spiritual call involved tough choices and a willingness to break free of old bonds.

It’s hard to imagine what it was like for him, becoming rich and famous beyond calculating by age 23, and having so many profound experiences at such a young age. His life was compressed. He owned everything worth owning, met everyone worth meeting, but he also had the innate intelligence to know that “there’s something more to life than boogying,” as he put it. He said his great fortune was learning what “something more” was, first through the spiritual music of Ravi Shankar, and then through the teachings of India’s yogis and gurus.

It’s hard to imagine what it was like for him, becoming rich and famous beyond calculating by age 23, and having so many profound experiences at such a young age. His life was compressed. He owned everything worth owning, met everyone worth meeting, but he also had the innate intelligence to know that “there’s something more to life than boogying,” as he put it. He said his great fortune was learning what “something more” was, first through the spiritual music of Ravi Shankar, and then through the teachings of India’s yogis and gurus. I wasn’t aware of how difficult it was to live his life, constantly targeted by exploiters, constantly deprived of his privacy—which was a moral issue that had to be confronted before writing this book. He had marvelous parents and he took guidance from the best teachers he could find, and those supports helped him eventually shed a lot of anger and bitterness. By the end of his life, he had achieved a very heightened, pure state of consciousness.

I wasn’t aware of how difficult it was to live his life, constantly targeted by exploiters, constantly deprived of his privacy—which was a moral issue that had to be confronted before writing this book. He had marvelous parents and he took guidance from the best teachers he could find, and those supports helped him eventually shed a lot of anger and bitterness. By the end of his life, he had achieved a very heightened, pure state of consciousness.